Reklama

3D tiskárny

AONN.cz

Sp┼Ö├ítelen├ę Weby

|

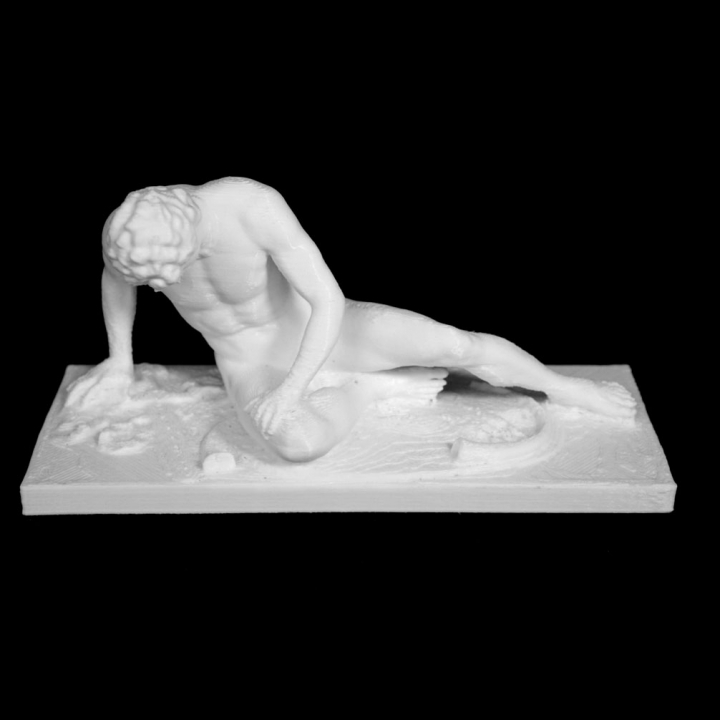

3D modely ARTThe Dying Galatian at The Capitoline Museums, Rome

Title The Dying Gaul Artist Unknown Date 1st or Century AD Roman Medium Marble Dimensions 37 x 73.16 x 35.16 inches Accession # Unknown Credit Sovrintendenza Captolina, Musei Capitolini, Rome, Italy The Dying Gaul—also called The Dying Galatian or The Dying Gladiator—is an ancient Roman marble copy of a lost Hellenistic sculpture thought to have been executed in bronze. The original may have been commissioned some time between 230 and 220 BC by Attalus I of Pergamon to celebrate his victory over the Galatians, the Celtic or Gaulish people of parts of Anatolia (modern Turkey). The identity of the sculptor of the original is unknown, but it has been suggested that Epigonus, court sculptor of the Attalid dynasty of Pergamon, may have been the creator. The copy was most commonly known as The Dying Gladiator until the 20th century, on the assumption that it depicted a wounded gladiator in a Roman amphitheatre. Scholars had identified it as a Gaul or Galatian by the mid-19th century, but it took many decades for the new title to achieve popular acceptance. The white marble statue which may have originally been painted depicts a wounded, slumping Celt with remarkable realism and pathos, particularly as regards the face. A bleeding sword puncture is visible in his lower right chest. The figure is represented as a Celtic warrior with characteristic hairstyle and moustache and has a torc around his neck. He lies on his fallen shield while his sword, belt, and a curved trumpet lie beside him. The sword hilt bears a lion head. The present base was added after its 17th-century rediscovery. The Dying Galatian is thought to have been rediscovered in the early 17th century during some excavations for the foundations of the Villa Ludovisi, then a suburban villa in Rome. It was first recorded in a 1623 inventory of the collections of the powerful Ludovisi family. The villa was built in the area of the ancient Gardens of Sallust where, when the Ludovisi property was built over in the late 19th century, many other antiquities were discovered, most notably the "Ludovisi Throne". By 1633 it was in the Ludovisi Palazzo Grande on the Pincio. Pope Clement XII acquired it for the Capitoline collections. It was then taken by Napoleon's forces under the terms of the Treaty of Tolentino, and displayed with other Italian works of art in the Louvre Museum until 1816, when it was returned to Rome. The statue serves both as a reminder of the Celts' defeat, thus demonstrating the might of the people who defeated them, and a memorial to their bravery as worthy adversaries. The statue may also provide evidence to corroborate ancient accounts of the fighting style—Diodorus Siculus reported that "Some use iron breast-plates in battle, while others fight naked, trusting only in the protection which nature gives."Polybius wrote an evocative account of Galatian tactics against a Roman army at the Battle of Telamon of 225 BC: "The Insubres and the Boii wore trousers and light cloaks, but the Gaesatae, in their love of glory and defiant spirit, had thrown off their garments and taken up their position in front of the whole army naked and wearing nothing but their arms... The appearance of these naked warriors was a terrifying spectacle, for they were all men of splendid physique and in the prime of life. The Roman historian Livy recorded that the Celts of Asia Minor fought naked and their wounds were plain to see on the whiteness of their bodies. The Greek historian Dionysius of Halicarnassus regarded this as a foolish tactic: "Our enemies fight naked. What injury could their long hair, their fierce looks, their clashing arms do us? These are mere symbols of barbarian boastfulness." The depiction of this particular Galatian as naked may also have been intended to lend him the dignity of heroic nudity or pathetic nudity. It was not infrequent for Greek warriors to be likewise depicted as heroic nudes, as exemplified by the pedimental sculptures of the Temple of Aphaea at Aegina. The message conveyed by the sculpture, as H. W. Janson comments, is that "they knew how to die, barbarians that they were." The Dying Galatian became one of the most celebrated works to have survived from antiquity and was engraved and endlessly copied by artists, for whom it was a classic model for depiction of strong emotion, and by sculptors. It shows signs of having been repaired, with the head seemingly having been broken off at the neck, though it is unclear whether the repairs were carried out in Roman times or after the statue's 17th century rediscovery. As discovered, the proper left leg was in three pieces. They are now pinned together with the pin concealed by the left kneecap. The Gaul's "spiky" hair is a 17th-century reworking of longer hair found as broken upon discovery. During this period, the statue was widely interpreted as representing a defeated gladiator, rather than a Galatian warrior. Hence it was known as the 'Dying' or 'Wounded Gladiator', 'Roman Gladiator', and 'Murmillo Dying'. It has also been called the 'Dying Trumpeter', because one of the scattered objects lying beside the figure is a horn. The artistic quality and expressive pathos of the statue aroused great admiration among the educated classes in the 17th and 18th centuries and was a "must-see" sight on the Grand Tour of Europe undertaken by young men of the day. Byron was one such visitor, commemorating the statue in his poem Childe Harold's Pilgrimage: I see before me the gladiator lieHe leans upon his hand—his manly browConsents to death, but conquers agony,And his drooped head sinks gradually low—And through his side the last drops, ebbing slowFrom the red gash, fall heavy, one by one... It was widely copied, with kings, academics and wealthy landowners commissioning their own reproductions of the Dying Gaul. Thomas Jefferson wanted the original or a reproduction at Monticello. The less well-off could purchase copies of the statue in miniature for use as ornaments and paperweights. Full-size plaster copies were also studied by art students. It was requisitioned by Napoleon Bonaparte by terms of the Treaty of Campoformio (1797) during his invasion of Italyand taken in triumph to Paris, where it was put on display. The pieced was returned to Rome in 1816. From December 12, 2013 until March 16, 2014 the work was on display in the main rotunda of the west wing of the National Gallery of Art in Washington D.C.. This temporary tenure marked the first time the antiquity had left Italy since it was returned in the second decade of the nineteenth century. (source, wikipedia) n├íhodn├Ż v├Żb─Ťr model┼»

|

©Ofrii 2012

| |||